An “End” to the Ethiopian Civil War?

Local students and professors address the issue and its coverage.

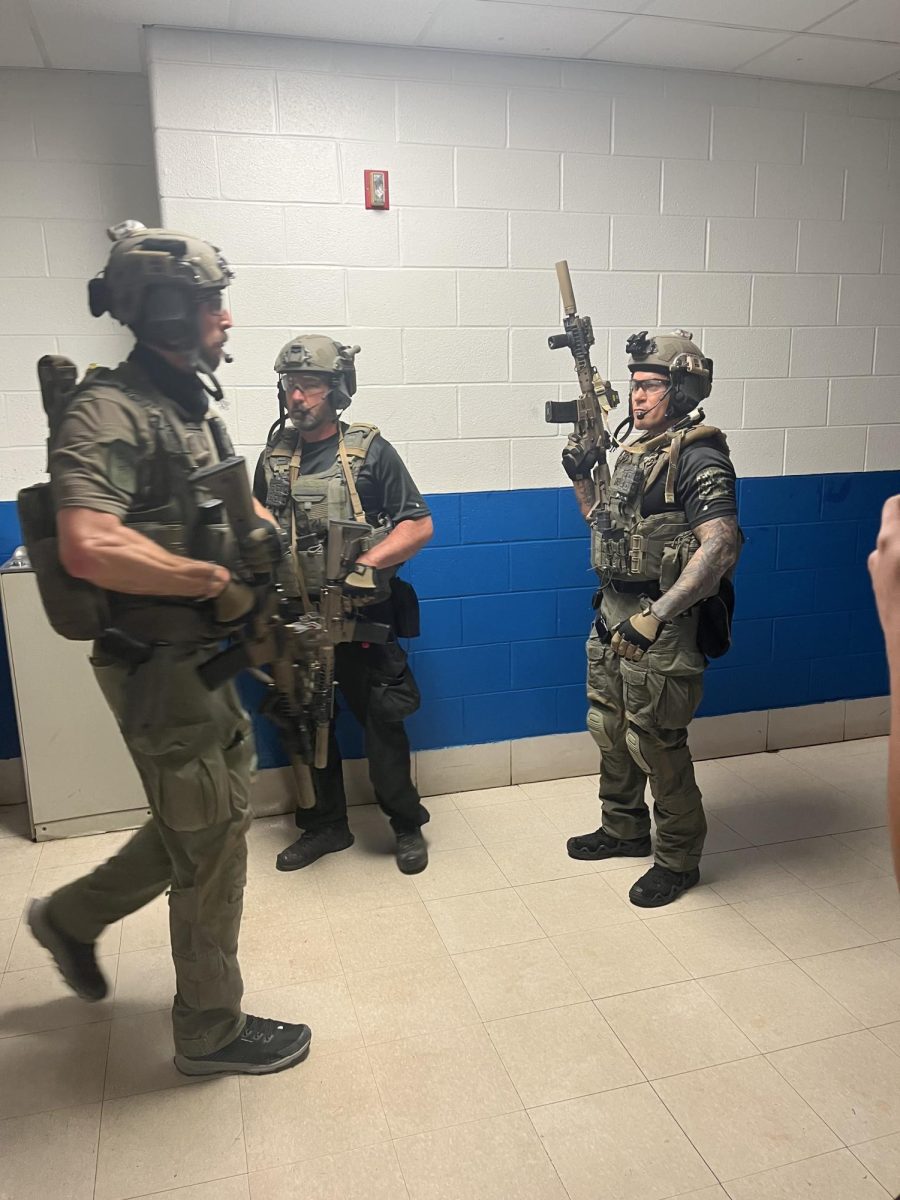

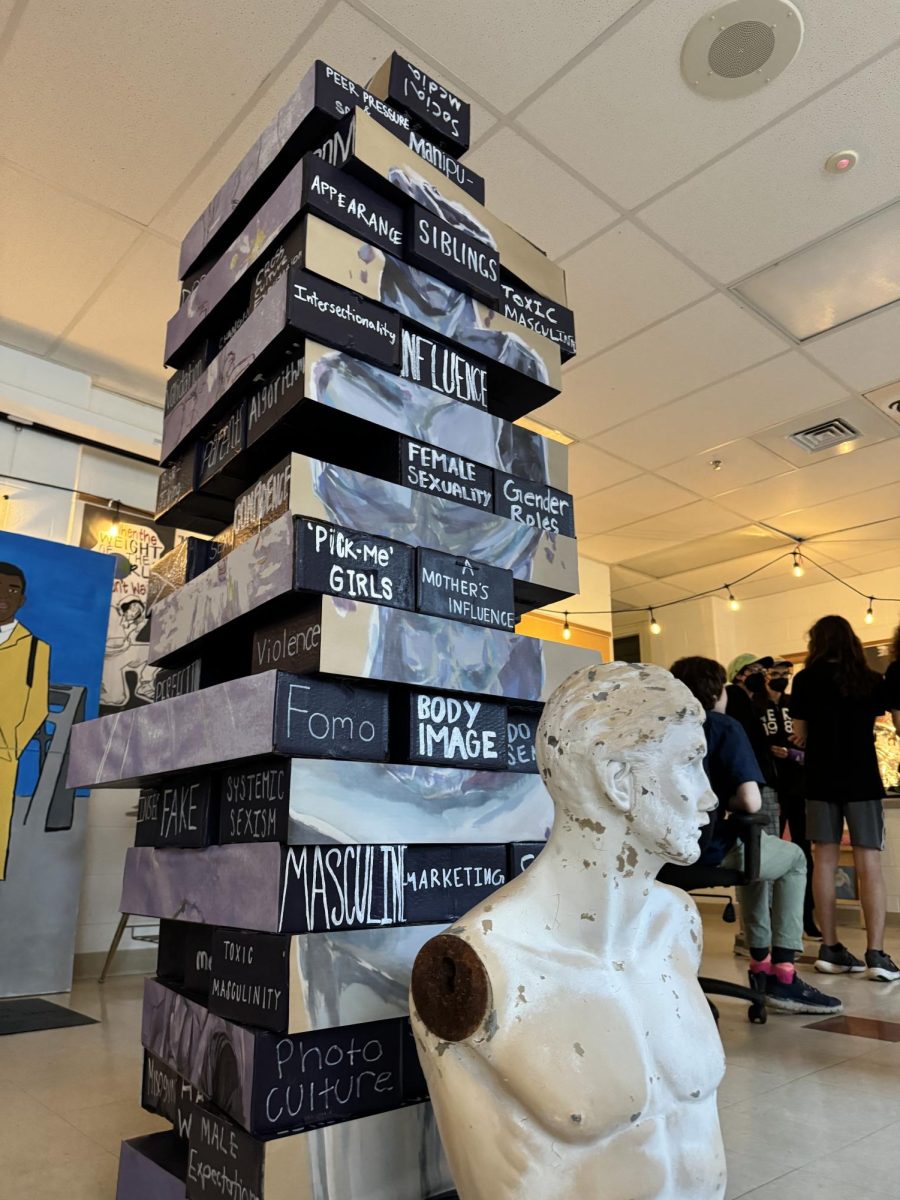

A soldier stands in front of the debris of a house in the Tigray region.

Media outlets across the world reported a peace deal was struck between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) on Wednesday, November 2. The deal intends to end a two-year war that began in November 2020 and led to half a million deaths among Ethiopians from numerous ethnic groups, particularly the Tigray.

“The peace deal is not sustainable…It’s a deal of surrender, it’s not a deal of peace,” stated James Madison University Professor Etana Dinka who teaches and researches the political history of the Horn of Africa.

Nahomen Berhe, a Tigrayan student activist, commented, “I don’t know, there’s a lot of confusion going around.”

She highlighted the need for proper media coverage of the war, referencing the ban on journalists in Ethiopia and the bias in Ethiopian media outlets as reasons why external coverage is needed. So far, Berhe considers the external coverage to be “weak” compared to the all-day coverage of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

“We saw with the Tigere [crisis], it took a while,” she explained. “It took a lot of protests, activists. It took so much energy for someone to hear us, and we just felt like we were screaming at a wall.”

Oromo activist Dereje Hawaz believes the lack of coverage isn’t a coincidence: “That is the tragedy of our world. It seems life doesn’t work the same based on geographic [location] or maybe even skin color, I should say.”

Although Professor Dinka agrees with Berhe and Hawaz on the poor quality of the coverage, he doesn’t believe it’s just about race.

“Every media outlet around the world covers the war in Ukraine, which is good because it brings awareness,” stated Dinka. “But the concern of the United States and many other Western powers for Ukraine and for the Horn of Africa is not the same. Some people say, ‘that’s because Europe is white and all of Africa is black: this is racist.’ This is too simplistic, to say the least. It’s not just the issue of race. There are strategic interests in this.”

Dinka notes that the Russo-Ukrainian War is “close to home” because Ukraine is “a major military and economic security partner of the United States, a major dependent of [the] World Bank and IMF, and a major global player.”

Dinka also points out that media coverage of the Ethiopian Civil War was curtailed by a “complete internet blackout, complete siege…no journalist would access what was going on…So in that sense, it’s understandable.”

One media outlet that stood out to Dinka for its better coverage of the Ethiopian Civil War was Al Jazeera. He isn’t the only one with a positive reaction. Berhe acknowledged, “Honestly, I’ve seen a lot of progress. There’s people who don’t share the same identity as me and know a lot about Tigray. I think that’s because they’re getting more and more info every day.”

Tensions initially rose when Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed assumed office in 2018, replacing TPLF leaders as the center of power in the Ethiopian government. Some TPLF leaders resisted Ahmed’s reforms, leading tensions to rise until the first attack was made by Tigray rebels on a government military base. In response, Ahmed ordered a military offensive in the Tigray region on November 4, 2020, leading to the outbreak of civil war as the Tigray retaliated.

Professor Dinka is no stranger to Ethiopia’s political climate. Dinka, however, doesn’t consider the recent deal to be one of peace. He noted how the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program and lack of concessions to Tigray indicate that the Ethiopian government wants Tigray’s surrender, not compromise.

Dinka isn’t alone in his doubt. Hawaz pointed out that other ethnic groups who fought in the civil war weren’t invited to the peace-making table. Hawaz referenced the Oromo Liberation Front, Sidama Liberation Front, and Afar Liberation Front.

“There was a great hope that change would come for Oromo and also for other oppressed nations and nationalities,” expressed Hawaz, believing that they too were wronged after the early months of the war saw the Ethiopian government going “door to door, [arresting] and [killing] people” or taking them to torture camps.

Others still doubt the peace deal after Tigrayan authorities accused the Ethiopian government of ordering drone strikes on the Tigrayan city of Maychew, just days after signing the peace deal.

Obse Abebe, a B-CC senior, serves as one of The Tattler's Editors-in-Chief. Her passion for journalism stems from her desire to empower the masses with...

Kira McClure • Dec 13, 2022 at 2:36 pm

This was an excellent article! I was very much educated on the topic as I am much more informed on domestic affairs and learned a lot that I’m sure I would have never have been educated on if not for this article. The article has a very distinct voice and makes the matter very captivating. I also very much agree with the sentiment that Ukraine is much more focused on in comparison to wars in Africa and Asia though this is discussed very often in the U.S. Again, a wonderful article and I very much enjoyed the read.