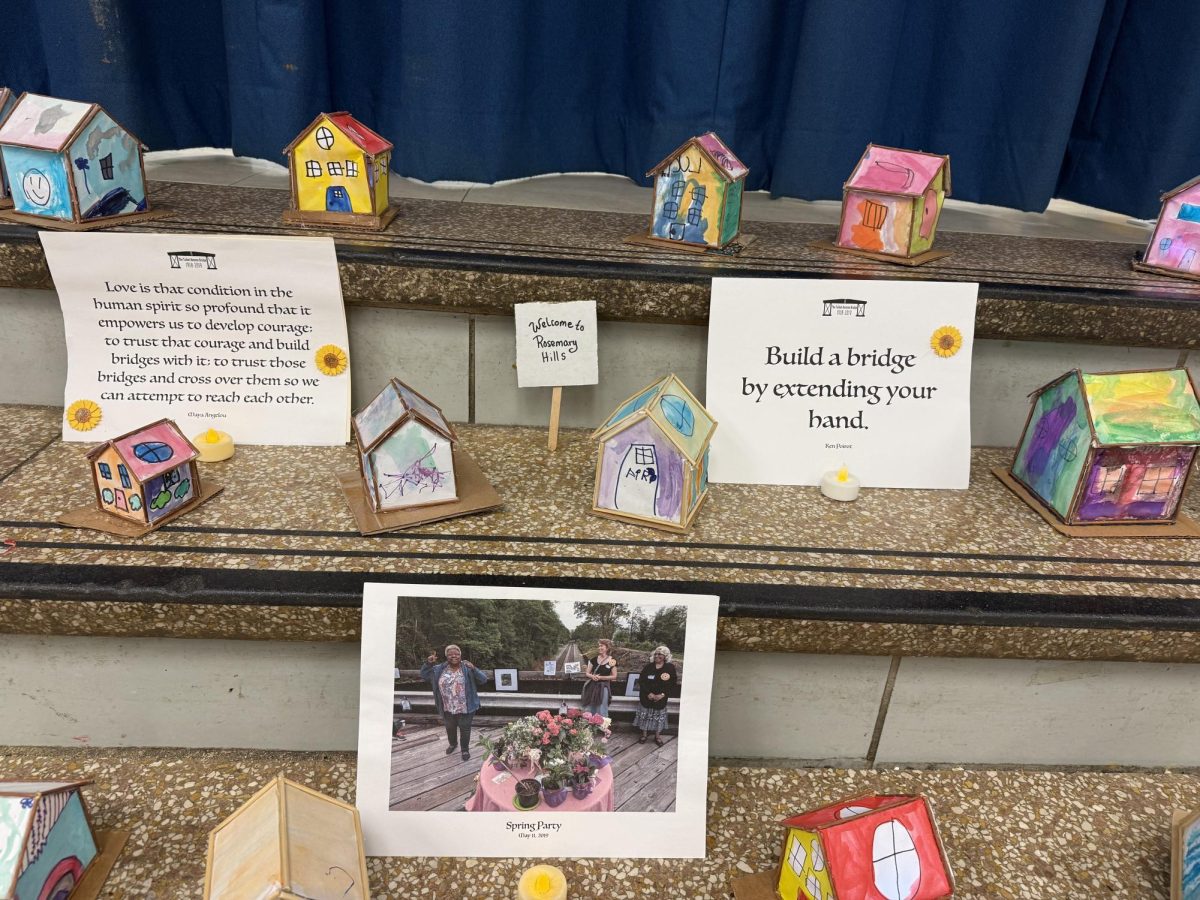

On November 16, over 100 people participated in a “Lantern Walk” over the newly rebuilt Talbot Avenue Bridge in Silver Spring, Maryland. They walked to celebrate their three neighborhoods – Lyttonsville, Rosemary Hills, and North Woodside – which were once divided by segregation, but now are connected.

The civic associations for the three communities recently asked Montgomery County to fund the construction of a park near the bridge that would serve as a memorial to Lyttonsville’s history and a place for residents to come together. Speaking to the crowd, longtime Lyttonsville resident Patricia Tyson commented, “I’m sorry my grandparents, mother and father aren’t here to see this gathering today. They dreamt of it.”

Students often complain that history is dry, boring, and irrelevant to our modern lives. But history is all around us. Lyttonsville, a neighborhood within B-CC’s boundaries, was founded by Samuel Lytton, a free African-American laborer for the Blair family. The community began with his purchase of four acres of land, but it now includes roughly 60 single-family homes on the edge of the area zoned to B-CC.

In 1917, Lyttsonville residents built the Linden School, a two-room schoolhouse with no running water. It served as the main school for Lyttonsville children through 1955. Montgomery County never spent taxpayer money on black schools, leaving families to raise money to fund the school.

The Jim Crow era cast a long shadow over Lyttonsville. For too long, Lyttonsville did not have running water or paved roads. Residents got clean water from a spring or a spigot that they paid $50 per year to the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) to use. Up until the 1960s, heavy rain meant that Lyttonsville residents could not get around, due to the dirt roads being too muddy to use.

Silver Spring was a “sundown town,” meaning that racial covenants written into deeds prohibited African Americans from owning houses in most of Silver Spring. This meant that African Americans from Lyttonsville could work in white people’s houses in North Woodside during the day, but they needed to be home by evening. Lyttonsville was one of the few communities in Silver Spring without racially restrictive covenants. The practice continued until 1968, when the Federal Fair Housing Act outlawed it.

Lyttonsville residents had very little access to the rest of Silver Spring. Their only route to commerce was over a one-lane wooden bridge constructed above a railroad track over one hundred years ago, named the Talbot Avenue Bridge. Charlotte Coffield, a lifelong Lyttonsville resident and advocate for her community, called the Talbot Avenue Bridge “our lifeline to civilization” during a 2019 celebration of the bridge. It was the only link between the predominantly White Woodside and the predominantly African-American Lyttonsville. Grocery stores, hospitals, and movie theaters were all on the North Woodside side of the bridge.

In September, Charlotte Coffield passed away. At the Lantern Walk, participants honored Ms. Coffield for her many contributions to the community. Tyson remarked, “The neighborhoods living and working together. That’s what we strive for. It takes people putting themselves aside and looking into the history of Lyttonsville — being interested in their neighbors.”

Following the opening of Rosemary Hills Elementary School in 1956, as part of school integration measures following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, students were bussed between the predominantly white Chevy Chase Elementary School and Rosemary Hills. This bussing plan faced significant opposition from some white families and was started and stopped multiple times. At various points, there were efforts to close Rosemary Hills Elementary School. The Coffields led the fight to save the school, and it has been open ever since. Rosemary Hills has educated tens of thousands of children who have gone on to B-CC. It is known as The Rainbow School because of its diversity.

In the 1960s, an advocacy group led by Lyttonsville residents Gwendolyn Coffield and Lawrence Tyson fought for urban renewal, and in 1968, Lyttonsville was designated a redevelopment area. Most of the houses, which were in poor condition, were demolished and replaced with more modern homes; roads were paved; and running water and street lamps were brought to the area. Some of the families, however, could not afford these new homes, and moved into the nearby Friendly Garden Apartments, a Quaker-built affordable complex. Also during the 1970s, Montgomery County seized sixty percent of Lyttonsville through eminent domain to build a WSSC Facility, an industrial park, and a Ride-on bus lot.

Pat Tyson, who has lived in Lyttonsville for more than seventy years, said Lyttonsville was the community on the “other side of the tracks” from North Woodside. Recalling when Lyttonsville’s roads were unpaved and there were fewer opportunities for its residents, Ms. Tyson said, “Even though we didn’t have what everyone else had, we were classy.” Myra Coffield, daughter of Charlotte Coffield, shared that her mother went to school in the two-room schoolhouse during segregation. She said, “My mom really valued education. She did a lot to support different programs for kids in the neighborhood.”

To learn more about the history of Lyttonsville, check out the exhibit at the Gwendolyn E. Coffield Community Center at 2450 Lyttonsville Road in Silver Spring.