Health Class Must Address Sexual Health Too

How can sex be surrounding everything in our society, yet we can barely discuss it?

June 9, 2023

Sex is an uncomfortable subject. While many adults (or quite honestly, teenagers) are sexually active and have questions or fears about sex, it’s rarely discussed in a direct manner, leaving increased room for confusion and discomfort.

When asked to recall the topics discussed in her sexual education class, a former B-CC student confessed, “All I remember from that class is to use a condom. And I don’t even have a very good track record with that.”

Zoe, a B-CC junior who took health care in Southern Arizona, shared, “For the birth control unit, they just taught us about abstinence, which really goes to show how in different parts of the country, there is really an inequity in health education.”

Another B-CC junior told me, “I lost my virginity when I was 14 years old. At the time, I had only been taught health in middle school. That didn’t really prepare me for the emotional aspects of having sex. Neither did health in high school when I got to that. Sex is a lot about giving yourself to another person and that isn’t really explored in the health curriculum. I wasn’t ready for the emotional attachment or investment that I felt with the other person, and that really messed me up. It’s taught solely as a physical thing.”

The biggest issue with not addressing sexual health in an educational setting is that most adolescents, especially young girls, can’t access the information elsewhere.

I asked Zoe what she would do if there was a problem with her sexual health, or if she felt something was wrong.

“I would probably google it. And then if I noticed that it wasn’t going away, I don’t know. I don’t think I would really go to a doctor because it would just feel stupid.”

Zoe shared her only experience at the OBGYN, saying, “A couple of my doctors were male, which I wouldn’t have preferred. I feel like they didn’t explain a lot of things. They kind of just said everything in ‘doctor terms’ and I had no clarity on literally anything about my body.”

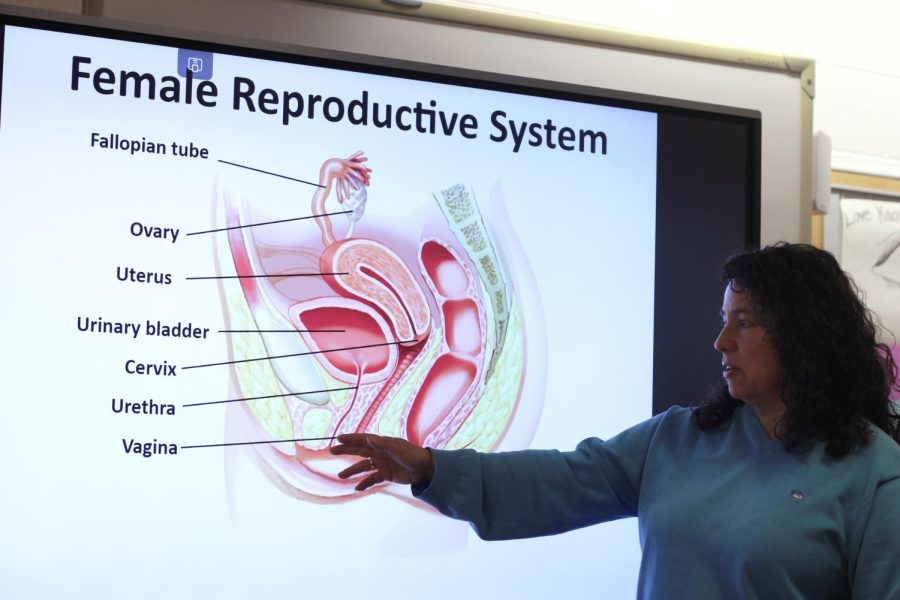

“Nobody knows anything about their genitals. They don’t even know what they’re called,” expresses Dr. Rachel Rubin, a local Bethesda urologist. She was recently featured in the New York Times with a story that covered women’s health issues and the lack of treatment available.

Her story documented a woman who after having a biopsy on her vulva area, could no longer reach orgasm. All of her doctors dismissed her problem, chalking it up to trauma from the surgery and reassuring her she would eventually go back to normal. She found no one who wanted to talk about pleasure-based sexual health and the source of her problem: her clitoris. All except for Rubin.

Part of Rachel’s unique take on sexual health is trying to facilitate honest conversation about bodies, and how they work. Practices like Dr. Rubin’s are rare. It’s shocking how little information is out there about sex (pornography doesn’t count) as well as, quite frankly, women’s bodies generally. As odd as it sounds, women’s health is a fairly new field of study. It was only in 1993 that the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Revitalization Act (which required the inclusion of women and racial/ethnic minorities in NIH-funded clinical research) was signed into law.

That makes us about 30 years into studying bodies that make up half the human population. The resulting misconceptions about sex, caring for yourself, and knowing how your body works, are no surprise.

When asked about the more important things no one wants to address, Dr. Rubin said, “The idea that women don’t orgasm from penetration. We have to talk about the clitoris more and how it works the same as a penis and offer more education to even be able to say those words and understand them.”

She has no trouble having awkward conversations about sex. She wants people to understand how to have enjoyable sex and learn the language to express all the things left to the imagination.

“I treat people from Washington DC, so I take the richest and smartest people on the planet, and I teach them very basic facts about their body parts and how they work which is pretty empowering and cool,” Rubin shared.

We ended our interview by talking about her Times article again, and its impact. “What was incredible about that article was all it was doing was giving women a mirror and showing them their own body parts and that was worthy of science fiction. It’s pretty embarrassing, right? It’s 2023, and that’s what constitutes science.”

Information is even more elusive for students who don’t identify as heterosexual and cisgender. A Bloomberg study published last March found that 1 in 5 high school students does not identify as heterosexual. Yet health curriculums that address different kinds of sex, let alone queer identities, are few and far between. Another junior, who asked to remain anonymous due to not being out, remarked, “I feel like [gay sex] wasn’t talked about at all [in health class]. I never felt represented.”

However, Rubin points out that this lack of representation, both in and beyond the health room, can actually lead to better communication between partners: “I would actually say with queer sex, because there are no scripts, no Hollywood movies to screw everyone’s brains up, there actually has to be better communication because you’re forced to talk with your partner.”

When sex is taught without addressing all of its complexities, a quotidian aspect of life somehow becomes taboo. How can sex be surrounding everything in our society, yet we can barely discuss it?

At B-CC, however, our progressive environment allows for more encompassing discussions. Ms. Lizarzo, a B-CC health teacher, recalls, “MCPS became the only county back in the 90s to even show how to put on condoms. We were quite progressive for the time.”

In her class, the most important thing is honesty. “MCPS has given me [diagrams] that the clitoris is not even on. I’m like, oh hell, some man did this? Then I talk about it because the girls don’t know, don’t even talk about it,” she lamented.

“I’m in the classroom every day, so I’m reminded of what it is to be fifteen. It sucks. How a girl feels about herself during high school is intense because most girls don’t like themselves, they don’t even know who they are.”

She makes a massive effort to make sure all students are included: “I do talk about if it’s two girls when they’re going they’re gonna have sex, how can we protect ourselves?”

She shared she wants her students to see themselves reflected in lessons, and learn to love themselves. She aims to create the health education she wishes she got in high school: “We all want to be accepted, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a teenager or you’re my age, we still want the same thing. To be loved without exceptions.”

She continues, “The program is not perfect, but it’s better than it used to be.”

Education about sex is far from an easy thing to approach. But facilitating the most honest and direct conversations possible is the best thing any of us can do to ensure students and adults alike can make good choices about their sex lives, as well as just understand their own bodies.

After all, your sexual health should be just that: healthy.

Gloria Trattles • Jun 10, 2023 at 8:08 am

Riley this is an EXCELLENT piece. Congratulations. So very well written and investigated. And so necessary.

Gloria Martinez Trattles BCC Mom 2020 and 2023